Dear Guest on my site,

I want to ask you for help.

I’ve just bought an object in Internet, and I haven’t even gotten it yet.

But I’m already in love with it.

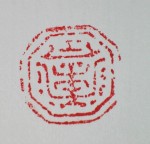

It’s a rather rare object that merits, and of course will have, an explanation of its origin. Let’s say that it should be a bronze seal used when China sent bales of silk to Japan. Its function was to make known the person who sent it and to guarantee that the bale arrived intact to its addressee.

What interests me now is this: what does it represent ?

A man on a horse?

A woman on a horse (usually women rode side-saddle)?

A monkey on a horse?

Maybe it’s not a horse, could it be a bovine: an ox or a buffalo?

And if it were the philosopher Lao-tse riding the animal?

The legend says that Lao-tse spent his entire life in the Emperor’s palace as custodian of the imperial archives. He spent years and years studying mankind and nature and the heavens, but he never wrote anything.

When he reached old age he decided to leave China and to ride a buffalo towards the mountains. When Lao-tse slowly arrived at the Han-Ku pass, the border-guard Yin-Hsi said to him, ”I will not let you pass until you put in writing all your wisdom. That way even future generations may benefit from it.” Lao-tse agreed and wrote the 81 short chapters of his “The Simple Way”, which we know as the ‘Tao Te Ching.”

Then the ancient sage continued his journey on the back of his buffalo towards the West (‘West’: the sunset, the end of life) and nothing more was ever known about him.

Well, I’d like to think that this small seal represents Lao-tse in his serene passage towards his sunset. But naturally what I imagine is only the hypothesis of an old man who is not terribly wise and hasn’t even a buffalo.

If this hypothesis makes you smile, dear Friend, pardon me. Still, it’s said that Lao-tse was born smiling. And smiling, I say goodbye to you. I shall be truly grateful if you would like give me the gift of your interpretation of this mysterious image.

Dear Franco,

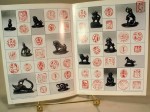

this very rare and enigmatic bronze seal, known in Japan as an “ito-in” or ’silk seal’, was likely cast in China around the 16th century during the Ming dynasty. The finial is a horse and rider, with an aperture for a cord on one arm. The octagonal base, considerably thinner than an ordinary seal, has an engraved design that looks like a strange Chinese character.

During the Muromachi period (1336-1573), Japan began to import great quantities of silk from China. Silk was one of the most important imports into Japan, and it is believed that ito-in were affixed to shipping cases containing silk. It may be that they were used to seal the package of silk, or that they were placed on receipts as proof of the transaction. Ito-in might also have been attached to silk shipments as a sort of certificate of the origin or quality of the goods. Ito-in means literally “thread seal.” They were also called “hakata-in,” or seals from Hakata, a trade port which played a leading role in the trade with China during this period.

Ito-in are bronze seals which are lighter in weight and smaller in size than traditional bronze seals. They were cast by a special method to make the inside of the grip hollow in order to minimize the weight, and the base was considerably thinner than ordinary seals. This indicates that ito-in were usually attached to something. Another name for them is “himo-in,” or “seals with cord.” Without exception, every existing ito-in has an aperture through which a cord can easily pass.

Experts differ on the question of whether these seals originated in Japan or China, and their origin is shrouded in mystery. Ito-in are not seals in the strict sense of the word — they were not made for use exclusively as seals. They have engraved designs which look at first sight like strange forms of Chinese characters, yet with very few exceptions, they cannot be read. Moreover, there are duplicates in the inscriptions as well as in the figures on the grips, so they were presumably cast from the same mold which was used over and over again. If ito-in were made as seals, there should not have been duplicates. The grips were richly decorated with animal or human figures, and they were cast in numerous shapes. Their overall features had more in common with Yuan and Ming dynasty seals than with Japanese seals of the same time period. Additionally, the clothing, hair styles and facial expressions of the human figures used for the grip are definitely Chinese, and the handling of animal motifs is permeated with a strong Chinese influence. Despite this, ito-in were regarded as seals in Japan, as the name itself reveals. They were even used as personal seals by many daimyo, including Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who used ito-in often in their documents.

Ito-in are also of interest due to their considerable influence on the development of netsuke, but that is another whole area of discussion unto itself. We have learned these details from an incredibly fascinating article, “Ito-In Japanese Silk Seals: An Inspiration for Netsuke?” by Kinya Niiseki (ARTS OF ASIA, July/August 1979) where seals and stamps similar to this one are copiously illustrated.

Condition of your ito-in is excellent, with wonderful patina and wear from centuries of handling. There is some minor loss on one side of the seal rim which is consistent with age and usage. Dimension : 1 ½” (3.8 cm) high x 1 1/8” (3 cm) wide and deep at base.

I hope you will find an answer you like to your interesting quiz.

Carol

Dear Franco,

intriguingly, I do happen to know what this is.

It is an advertisement.

In the 16th century, in a certain distant part of Mongolia, close to Russia, there was a tribe called the Belli who used to get into a lot of scraps with their neighbours – it didn’t matter who, they just liked to fight. Unfortunately, their only hospital was at the capital some 150 miles away across the steppes from where they were usually getting into fights, so an enterprising chap one day set up a series of Donkey Ambulances (this was long before the piston engine had been invented) to get the wounded as quickly as possible back to the hospital and, once patched up, get them back again to the front where they could get wounded all over again. Gosh, it was fun.

As a good entrepreneur, he realized the value of advertising, so made a series of little seals depicting a wounded man (in this case quite badly wounded, with one arm missing, holes all over him, etc.) being carted rapidly off to hospital. Being a clever lad, he sold an insurance policy to the fighters so that in exchange for two yaks and the use of at least one of their wives while they were away at the front, he would guarantee to have a donkey at hand ready to whisk him off to hospital in the event of a little problem with weaponry. The seal part was for impressing on his T-shirt the seal which meant he’d paid up (or was, as he was being wounded, paying up in the case of the spare wife since the entrepreneur was clever enough never to go anywhere near the battlefield preferring to stay in bed bonking his premiums).

I’ts made about 1535 (which is just after three o-clock, when he tended to awaken

from his lunchtime bonk). They are quite rare.

All the best

Huifeng jushi

dear Franco,

granted that it seems to me it’s a water buffalo rather than a horse, as the former, in the tradition of the Extreme-Orient has a dignity different than the latter (only different, not more, to be clear), it seems difficult to me that it represents a rider in the position which is usual for riding a water buffalo; granted that the ideogram “niu” has a very wide spectre of meanings that include cow, bull, buffalo, ox, etc.; granted that the portrayal of the person in your seal is not detailed sufficiently to identify the subject with certainty; and, consequently, granted that one cannot refuse your hypothesis of recognizing Lao-tse, notwithstanding that he is usually portrayed

as a bearded old man; granted all these things, could it not be a child then on the back of a water buffalo?

As you know, this is an iconography widely diffused in Chinese art, beginning with the Song period (960-1279), during which many paintings portrayed this subject. Often the child rides on the bovine’s back playing a flute, but it is not rare that the instrument

does not appear, and that the child rides it gently, without doing a thing gently. I know that this image visually translates the saying

“chun feng de yi”, literally, “to have a happy life under the wind of spring”, which, briefly, means living without worries of any sort,

just as a child can ride a water buffalo without worries because it is the most docile of all docile animals.

I don’t know if your object represents this theme, but among your hypotheses this was lacking, and I took the liberty of suggesting it.

Bye for now, Francesco

Thanks, Francesco, you’re truly fantastic!!

Since I’m writing you while gently sitting sideways on a water buffalo, so please excuse me if the letters of my Mac are a bit wobbly.

I accept with gratitude and sincere enthusiasm your interpretation, which seems to me, as it often happens with you, both scientifically brilliant and emotionally intense.

I suggest only a minimum modification where your interpretation seems to allude to a possible identification between me and the person portrayed on the water buffalo.

Just substitute where “child” is written with the more pertinent “in his second childhood”.

So your:

“Often the child rides on the bovine’s back playing a flute, but it is not rare that the instrument does not appear, and that the child rides it gently, without doing a thing gently.”

becomes, and much more appropriately :

“Often an old man in his second childhood rides on the bovine’s back playing a flute, but it is not rare that the instrument does not appear, and that the old man in his second childhood rides it gently without doing a thing. Gently.”.

Dear Friends,

your conversation, if I compare it with what I hear every day at 6 p.m.

at the Mad Hatter and the March Hare’s tea-party, is raving mad.

And exactly because of that it is infinitely more delightful.

I say this even though I know I shouldn’t make personal remarks.

Franco,

I believe this is a baby (Lao-tse is usually depicted wearing a beard and this animal is too thin for a water buffalo). I believe it is a baby (a son, of course) riding a horse representing speed, which makes it a wish for the speedy arrival of male descendants. This was every man’s wish in China.

Il filosofo Wang Yang Ming riprese agli inizi del XVI secolo l’ideale innocenza del bambino quando affrontò il tema della natura dell’uomo alla nascita. Da allora, per i letterati dell’epoca, influenzati massicciamente dal neoconfucianesimo, divenne imperativo mantenere il “cuore di bimbo” (ttong xin 童心). Nel suo saggio “Sul cuore di bimbo” (Tong xin shuo 童心 說), Li Zhi (1527-1602) scrive: “Il cuore del bimbo non è mai falso, ma puro e autentico… Se perdi il tuo cuore di bimbo, perderai il tuo cuore autentico”.

Questo interesse da parte delle classi sociali colte portò a un rinnovato interesse per i ritratti di pastorelli con varie modalità artistiche, rappresentanti la vita spontanea e spensierata che i letterati idealizzavano. In particolare, un tema popolare dell’arte Song erano i ragazzi che portavano al pascolo bufali.

“Tornare a casa” in groppa a un bufalo era anche una metafora usata per spiegare le fasi della pratica e dell’illuminazione chan, così come la visione romanticizzata dell’infanzia spensierata poteva essere un simbolo della mente illuminata dei neoconfuciani.

Tuttavia i pastori di bufali nell’arte Song di solito sono adolescenti. Col passare del tempo, l’idealismo Ming, l’interesse crescente per il ritratto di ragazzi e il riconoscimento dell’infanzia come fase distinta della vita, portò a dipingere pastorelli sempre più giovani.

Ho tratto liberamente queste note da Children in Chinese art, di Ann Elizabeth Barrott Wicks.

Folcloristica nota finale: quando siamo andati a prelevare quegli ottimi spaghetti, la “simpaticissima” Elena aveva proprio alle spalle una bottiglia di grappa a forma di ragazzo in groppa a un bufalo;come si diceva nell’antica Cina, FBL (fa balà l’oech!).

Tra chi scrive i commenti qui sopra ci sono alcune tra le massime autorità al mondo di arte e cultura cinese :

veri grandi che dedicano il loro tempo per rispondere ad uno sconosciuto da cui non c’è da aspettarsi né soldi né gloria.

Rispondono, scrivono regalando la propria scienza, condividendo le proprie emozioni, inventandosi non solo un nome di fantasia, ma una intera storia di straordinario humour. Che lezione per i molti presuntuosi tromboni nostrani che il più delle volte nemmeno si degnano di risponderti

e se lo fanno, quando lo fanno, è solo per dirti scocciati che sono presissimi e non hanno tempo. “Non hanno”, ma qualcos’altro.